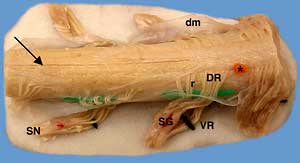

The spinal cord is a long cylinder of nervous tissue with subtle cervical and lumbar (lumbosacral) enlargements. The enlarged segments contribute to the brachial and lumbosacral plexuses. In the above image, showing a brain and spinal cord from a neonatal pig, the spinal cord and spinal roots are enveloped by dura mater.

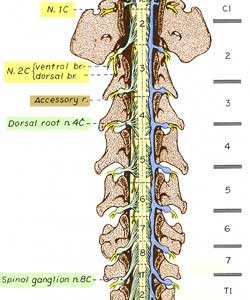

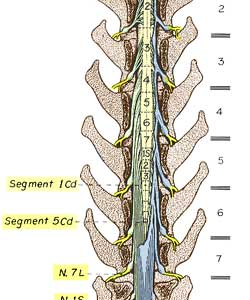

The spinal cord is divided into spinal cord segments. Each segment gives rise to paired spinal nerves (click left image). Dorsal and ventral spinal roots arise as a series of rootlets. A spinal ganglion is present distally on each dorsal root. The canine spinal cord has 8 cervical, 13 thoracic, 7 lumbar, 3 sacral and 5 caudal segments. The following table compares species.

The spinal cord is divided into spinal cord segments. Each segment gives rise to paired spinal nerves (click left image). Dorsal and ventral spinal roots arise as a series of rootlets. A spinal ganglion is present distally on each dorsal root. The canine spinal cord has 8 cervical, 13 thoracic, 7 lumbar, 3 sacral and 5 caudal segments. The following table compares species.

Spinal cord segments in different species (for reference purposes):

Dog: 8 cervical; 13 thoracic; 7 lumbar; 3 sacral; & 5 caudal = 36 total

Cat: 8 cervical; 13 thoracic; 7 lumbar; 3 sacral; & 5 caudal = 36 total

Bovine: 8 cervical; 13 thoracic; 6 lumbar; 5 sacral; & 5 caudal = 37 total

Horse: 8 cervical; 18 thoracic; 6 lumbar; 5 sacral; & 5 caudal = 42 total

Swine: 8 cervical; 15/14 thoracic; 6/7 lumbar; 4 sacral; & 5 caudal = 38 total

Human: 8 cervical; 12 thoracic; 5 lumbar; 5 sacral; & 1 coccygeal = 31 total

Note: Per region, segments and vertebrae are numerically the same,

except for only seven cervical vertebrae and many more caudal vertebrae.

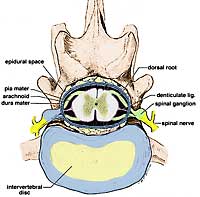

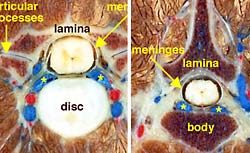

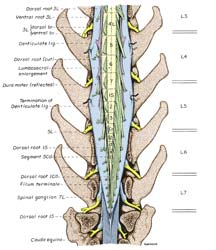

The spinal cord and spinal roots are enveloped by meninges and housed within the vertebral canal. The epidural space, situated between the wall of the vertebral canal and the spinal dura mater, contains a variable amount of fat. Within dura mater, the spinal cord is suspended by bilateral denticulate ligaments and surrounded by subarachnoid space filled with cerebrospinal fluid. Dorsal and ventral spinal roots unite to form spinal nerves which exit the vertebral canal at intervertebral foramina. An intervertebral foramen is formed by adjacent vertebrae and by the intervertebral disc joining the vertebrae.

As a result of differential growth of the spinal cord and vertebral column, most spinal cord segments are positioned cranial to their nominally corresponding vertebrae. However, spinal segment length is variable along the spinal cord in our domestic mammals. Segments become progressively shorter from the C3 to T2. Then they elongate so that segments at the thoracolumbar junction are within nominally corresponding vertebrae. Thereafter, segments progressively shorten until the cord terminates in a terminal filament of glia. (The term "conus medullaris" refers to the cone-shaped cord region between the lumbosacral enlargement and the glial filament.)

Since spinal nerves exit the vertebral canal at nominally corresponding intervertebral foramina, spinal roots must elongate when spinal cord segments are displaced cranially. The term cauda equina (horse tail) refers to caudally streaming spinal roots running to intervertebral foramina in the sacrum and tail. Damage to the cauda equina affects pelvic viscera and the tail. Cauda equina epidural anesthesia (putting anesthetic into the epidural space to block conduction in spinal roots) is a common obstetrical procedures in cattle.

Because vertebrae can be palpated and visualized in ordinary radiographs, unlike spinal segments, it is clinically useful to know locations of spinal cord segments relative to vertebrae. Typically (for most dogs) the cervical enlargement is centered at the C6-7 intervertebral disc; spinal segments of the thoracolumbar junction are within nominally corresponding vertebrae; the sacral segments are within vertebra L5; and the functional spinal cord terminates at the L6-7 vertebral junction. (Termination is about one vertebra further caudally in small dogs, less than 7 kg.)